Have you ever wondered where you will go after this life ends?

While I have been serving monthly at a Grief and Enrich support group, one of my uncles passed away a couple of months ago. My family and I attended his funeral in Japan, held in the Buddhist tradition. He was my father’s older brother, and we were all close.

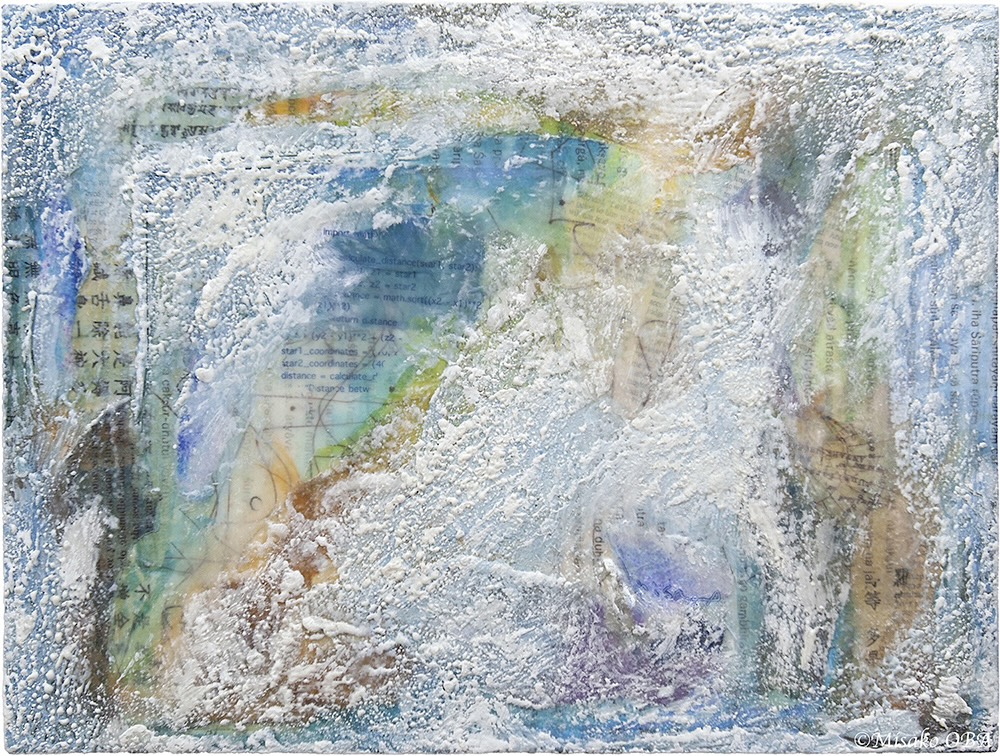

I had mixed feelings about his death and the funeral. As I began researching more about Buddhist beliefs—especially what happens after death—I felt uneasy, deeply sad, even regretful. I couldn’t help but create something; I needed to let my emotions and thoughts out through art.

As a Christian, I know where I believe I am going after death. I asked my cousin, my uncle’s son who is two years older than me, “Do you know where he is going after death?” He answered, “I don’t know.”

I’m fairly certain almost no one at the funeral—except the monk—knew the detailed meaning or content of the Sutras being chanted. It felt like something done simply because it is what people do. During the chanting, as the monk read the Sutra, I suddenly remembered the character Screwtape from C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. I almost imagined him floating around the funeral, perhaps laughing quietly…

What Buddhist Funerals Mean — and Don’t Mean

The purpose of chanting Sutras at funerals is to pray for the deceased—to ask Buddha for protection and hope for a peaceful departure. In Japanese, “Meifuku” expresses a wish for the deceased to be happy after death, but it does not mean heaven in the Christian sense. It simply means wishing them peace in the underworld, the world after death.

In Buddhism, the afterlife is part of the cycle of reincarnation, and one’s next life depends on karma. The Six Realms (Rokudō) determine one’s rebirth:

- Tendō (Heavenly Realm) – Happiness, though still bound by earthly desires

- Ningendō (Human Realm) – Suffering and joy, with opportunities for spiritual training

- Shuradō (Asura Realm) – A realm of conflict and anger

- Chikushodō (Animal Realm) – Instinct, ignorance, survival

- Gakidō (Hungry Ghost Realm) – Insatiable hunger and desire

- Jigokudō (Hell Realm) – Fear, suffering, punishment

Only Tendō offers something like “peace,” yet even there, once that life ends, one returns to the cycle of rebirth. There is no true liberation.

So within strict Buddhist teaching:

– “Rest in peace” is uncertain.

– The afterlife itself may be a world of suffering.

My Regrets, and the Visit to His Hospital Room

I felt sorry and kept feeling regretful—sad that I couldn’t be part of my uncle’s salvation. I tried, but could I have done more? I didn’t want to push too hard. My cousin (his daughter) had told us that their family had no interest in Christianity or any religion. They are “Buddhist” in the common Japanese sense—culturally, not spiritually.

I visited my uncle in the hospital during his late-stage stomach cancer. I brought my mother’s pastor, hoping there might be a chance to share the Good News. But my uncle was already too weak to respond, and the pastor didn’t initiate anything directly about salvation. I also didn’t want to hurt or disturb him and my cousin emotionally. Still, we prayed aloud for his peace, comfort, and possible recovery. My cousin allowed us to do the prayer. The pastor read Psalm 23:1 and a few verses.

As I reread Psalm 23 later, I sensed there may still have been a possibility that God reached him in a way we could not see. We simply don’t know.

Yet I keep thinking: I wish I had been more bold.

But at the same time, I’m not sure I could have. Speaking about salvation can imply acknowledging death, and I didn’t want to hurt or discourage him. After the hospital visit, I felt powerless.

All those emotions eventually led me to create the artwork—layered with many elements, covered in white like pure snow. Despite the heaviness, there is still beauty. The beauty of the life he lived. He was always cheerful, energetic, and a good brother to my father. We have many fond memories with him, my family, and his children, my cousins.

About the Text Inside the Artwork

The text in this work includes the Heart Sutra (般若心経) of Buddhism in the original classical Sanskrit (public domain) and Kanji. I prepare these mixed media materials before painting—this time, text from the Sutra. Right: a detail of my artwork Where Are You Going?

The Heart Sutra is a widely known Buddhist sutra in Japan. I heard it at my uncle’s funeral. In Sanskrit, it translates to “The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom.” I didn’t know that until I

researched it this time—and I’m sure most Japanese attendees, including my aunt, cousins, and many others, didn’t know its meaning either. I painted over it with encaustic, carrying all my mixed feelings—thinking about Japanese people’s indifference to the meaning of sutras and to questions of salvation.

*Unlike the Bible, since the Buddha’s death, his teachings were passed down orally through recitation, because the written culture developed more than two hundred years later.

Religion and Culture in Japan

In Japan, Christians are less than 1%. Most Japanese people live within a blended Shinto–Buddhist culture without practicing either, and they don’t see themselves as believers. Many foreigners know more about Buddhism or Zen than most Japanese. Religious rituals in Japan are often simply customs, not faith.

That’s why many Japanese people have Buddhist funerals, store ashes in temple graves, visit Shinto shrines for New Year or major life events, and enjoy Christmas or Western-style church weddings—with no religious meaning behind them. These are cultural, not spiritual.

Interestingly, according to Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, the number of religious “memberships” is about 181 million, far more than the country’s population of about 124 million. People usually don’t have a specific religion or faith; instead, they are “flexible,” participating in multiple traditions at once. This reflects exactly what I described above.

So when it comes to funerals, most Japanese don’t even think about where they will go after death. Many would say they become “mu” (emptiness), meaning nothing.

My Parents’ Story

Although I have spent many years in the U.S. and some time in Europe, I was born and raised in Japan. I understand Japanese culture and social customs, especially regarding religion. My parents were typical Japanese—culturally Buddhist/Shinto. But about ten years ago, both became Christians after I shared the Good News with them. First my father, then my mother a year later. Honestly, it felt like a miracle. I never imagined it for many years. I still often feel thankful about this. God is great.

All I needed to do was tell them about Jesus and how to receive salvation. (Previously, I told them from time to time how God and Christian friends were so loving through their actions, especially when I was in a rare medical condition. I consider Christianity not a “religion” or set of rituals, but a personal relationship with God.)

Yet when I first became a Christian myself—in graduate school in the U.S.—they were shocked and didn’t like it. Again, Christianity is less than 1% in Japan. In general, Japanese people are very cautious about churches and organizations because there were historically multiple deadly incidents and crimes by religious cults. I have been very cautious too because I had been a journalist / photojournalist.

A Choice, Hopefully to Make

There is still so much I don’t know about Buddhism or Shinto gods. But my point is: most Japanese people who identify as Buddhist or Shinto are not actually believers. I don’t blame them—this is cultural. Unless they are exposed to other worldviews, they don’t even have an opportunity to consider different perspectives. They simply follow tradition.

I do know where I am going, and where my parents are going, after death—and I am grateful. We are going to Heaven, where Jesus is. A better place than this world, according to the Bible.

I learned this is a choice. My choice, your choice, our parents’ or friends’ choices. But if people—like most in Japan—don’t even have the opportunity to hear or know the Good News, that is unfortunate. This is one reason I pursued fine art instead of continuing in journalism: to share my perspective through creativity.

Side: Detail of Where Are You Going? — You can see some computer languages. in my work. I often combine timeless, ancient elements with contemporary ones as my style.

Current series How Can You Show Love…?

* One-of-a-kind art in a similar style from the current series can be viewed and available here— many of the white encaustic mixed-media pieces have already sold out.

AND

* For your joy✨—no matter what circumstances you are in— White Breath covered in white encaustic was created as a series! Enjoy the Joyous Collection 2025/2026. ✨